“Martial Artist Does His Thing”

January 14, 1979

Missoulian Newspaper

(Republished with Permission)

Article By Kathleen Johnson

Photos By Howard Skaggs

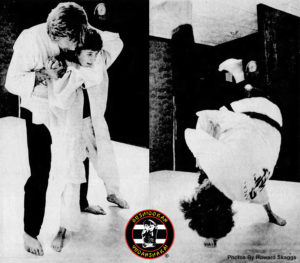

They meet in silence in the middle of a mat – the timid student and her instructor in the art of sell defense.

Gingerly, she reaches for his white gi (martial arts apparel). In a spilt-second, he flings her off the mat, whirls her through the air and slaps her onto the floor. She gets up, rearranges her hair and smiles.

Jim Harrison is doing his thing. The three-time All American Karate Grand Champion is demonstrating falling techniques to his women’s self-defense class in his Samurai Martial Arts Training Center, 1290 South 3rd St. West.

[. . .]

As two young men practice kicking in the background, Harrison demonstrates how to flip an assailant, how to rake his eyes or mouth, how to devastate the attacker with one swift move.

The students’ attitude toward Harrison is reflected in the atmosphere of the class – subdued but friendly – because Harrison does not believe in strict formality as do many Shi-hans.

The students sit cross-legged against huge punching bags at the edge or the mat, each bag sporting a white, yellow, orange, green, brown or black belt. The belts are symbolic of the martial arts rating system, white being the lowest and black being the highest achievement attainable [. . .]

Harrison began teaching karate, judo and jujitsu 15 years ago in Kansas City, Mo. He called his business “Bushidokan” Japanese for “Warrior’s Way.”

Harrison said he chose the word to symbolize his theory of martial arts – that they were primarily a means of self-defense and secondly, a sport.

When his students began applying for promotions with the United States Karate Association, one of the half-dozen karate governing organizations in the U.S., the association sent back their applications with the word Bushidokan listed as the type of karate taught.

Since Harrison had developed his own style of karate, a conglomeration of other more traditional styles, he adopted Bushidokan as name of the new discipline.

[. . .]

Back on the mat, the women watch Harrison grab a student by the neck, sneak up from behind or pin her arms at her side. Each time, the martial arts novice escapes his grasp.

The students are learning well.

They laugh as one spirited student flips Harrison, makes a defiant fist and parades back to the line.

“Did you eat raw hamburger before you came to class today?” he calls after her.

He jumps up, surveys the group and says, “Okay, then, I’ll find one more my size.”

With that, a 14-year old girl approaches Harrison. He turns her around, grabs her from behind as to choke her. She takes a deep breath, squats and hoists her instructor over her shoulder, slamming him against the cold, hard mat.

With that, a 14-year old girl approaches Harrison. He turns her around, grabs her from behind as to choke her. She takes a deep breath, squats and hoists her instructor over her shoulder, slamming him against the cold, hard mat.

But Harrison doesn’t stay down long. He has spent about all of his 41 years kicking, flailing his arms, falling down and getting back up – all in split-seconds.

[. . .]

In Kansas City, Harrison owned four Bushidokan martial arts schools.

When the martial artist moved to the Garden City [Missoula], he changed the name of his school to Samurai Martial Arts Training Center to avoid confusion between the name of the school (Bushidokan) and the style of martial arts (Bushidokan).

A samurai, the black belt explained, is a member of the ancient ruling and warring class in feudal Japan.

Harrison knows a great deal about the Orient, having studied and competed there in the sixties. He speaks “technical” Japanese and can ramble on for hours about the history and development of the martial arts.

His expertise and beliefs are reflected in the day-to-day operations of the school. The Samurai Martial Arts Training Center is a family owned business. Harrison and his 20-year old son, Shawn, are the chief instructors. Shawn is a first degree black belt in judo and karate who is vying for the 1980 Olympics. (Shawn won first place in the young men’s division of the U.S. Judo Association competition in St. Louis recently.)

[. . .]

“A lot of people are hung up on the ego thing. My students aren’t. The people in this school aren’t trouble makers – they want to avoid trouble. They learn confidence, not arrogance. They don’t have anything to prove,” he said.

Harrison estimated that 90 percent of his students enroll to learn sell defense, although only about 40 percent admit it. After they learn the basic or self defense, the students become more interested in the martial arts as a sport, Harrison said.

Students can choose from a fare of basic, intermediate or advanced judo or karate, basic or advanced women’s self defense, kobu-jitsu (small weaponry), a form of kick-boxing and full-contact karate.

[. . .]

The martial artist said enrollment in his new school exceeds his expectations, with some 90 students attending the center on a regular basis.

When asked why he has spent his life learning to fight, Harrison responded without hesitation.

“The martial arts look superior to getting out there and hitting each other in the head.”

Harrison, who was a policeman in St. Louis for several years, said he always had astrong desire to learn karate but was unable to find a teacher until the age of 17 when he had his first karate lesson.

It was love at first karate chop.

Harrison began to study under the few martial arts instructors in the U.S. at the time, gaining ability and strength with each class.

Since those early days, Harrison has attained enough achievements to fill a brochure.

He holds a three-time AAU Regional Championship title in judo, has trained three Grand National Champion Karate Teams and his Junior Judo Team hasn’t been defeated in regional competition in 11 years.

In 1974, Harrison was selected to coach the U.S. National Karate Team, which was undefeated in 57 matches. He coached the team again in 1975 and 1976 when they toured the Orient and Europe.

Harrison has appeared on ABC’s “Wide World or Sports” as the chief referee for the U.S. and World Championships.

In the 18 years he has been teaching, Harrison has seen 10,000 students on his mat, 78 of whom won first place in national martial arts competitions in their devisions.

He also has written articles for “Professional Karate” and other martial arts publications.

And the list goes on.

[. . .]

During the 12 hours he spends in his spacious school, Harrison frequently challenges his sons to a karate, judo or jujitsu match.

Or, to add a bit of spice to life, he challenges Shawn to a duel with a bo (a five-foot long stick). Harrison gives his son a run for his money.

The Shi-han also works with some of his favorite martial arts weapons – nun-cha-kas, which are two sticks held together with rope; sais, which look like pitch forks; tui-fas, which are Japanese well-wheel handles, and ko-bos, small, short sticks.

The Shi-han also works with some of his favorite martial arts weapons – nun-cha-kas, which are two sticks held together with rope; sais, which look like pitch forks; tui-fas, which are Japanese well-wheel handles, and ko-bos, small, short sticks.

The visitors in the peanut gallery who watch Harrison whirl the weapons around wonder if the weapons are “dirty”.

Harrison maintains they are not.

“There’s no such thing as the dirty fight. There’s no such thing a a clean fight. If a guydraws a .38 and is going to drill you, is that clean? You crack him across the head, is that dirty?”

With that, Harrison turned to to his women’s self-defense class and said, “The only weapon worse than karate is a loaded purse.”

He chuckled, bowed to his class and strolled off the mat.